New York Times: Source

THE Simonds family can document their roots going back to White-Eye Simon, an Indian listed on a Mashantucket Pequot land-claim petition in 1725, and Simeon Simons, a Mashantucket Pequot who served as George Washington’s bodyguard and servant through the Revolutionary War.

Yet today, none of the 300 or so Simonds clan members may live on Mashantucket Pequot land or share in the tribe’s enormous wealth.

The Simonds are no longer even recognized as Mashantucket Pequots, although their known and documented ancestors (whose names have various spellings) are frequently mentioned in the tribe’s official history.

Although nobody disputes the pedigree, the extended family does not qualify for tribal membership because the last Simonds stopped living on the reservation sometime in the 1860’s. Most of them now live in southeastern Connecticut or in the three southern counties of Rhode Island.

Because of a technicality in modern Mashantucket law that only allows people with ancestors listed on a 1900 and 1910 reservation census to become tribal members, the Simonds are being denied membership in the tribe.

The rules that keep the Simonds out were rewritten by the tribe in 1984 — a change the family claims was made specifically to exclude them. Although state and Federal law give Indian tribes absolute authority over their membership, lawyers for the Simonds are preparing to argue in Federal court that the membership rules that are excluding them are the result of actions by the Federal Government as well as by the Mashantucket Pequot tribal government.

The Simonds say their federally recognized civil rights were violated by the 1983 Mashantucket Pequot Land Settlement Act, a special act of Congress that granted the tribe Federal recognition and eventually allowed the tribe to build a bingo hall and a casino.

Only descendants of Martha George and her four daughters are currently recognized as members of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation.

The George clan now numbers about 370 people who live on or near the reservation in Ledyard.

According to United States Bureau of Indian Affairs guidelines, a single extended family, descended from one person with Indian ancestry, is not a tribe.

Although admitting the Simonds clan would allow the Mashantucket Pequot to more closely fit the Federal criteria for an Indian tribe, the Mashantucket Pequot claim state and Federal laws give them the unchallenged right to decide tribal membership.

But the Simonds say the current membership laws can be challenged in Federal court.

Ancestors of the Simonds are listed on an 1858 census of the reservation and on every surviving census taken before that. But they are not on the 1900 or 1910 lists.

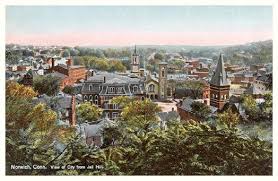

During the late 1850’s and 1860’s the Simonds family left the reservation to find work in Griswold, said Joan Simonds, 42, of Norwich.

As the family grew, members settled throughout the Norwich and New London areas, some eventually setting up small businesses, a few even entering professions like law and medicine.

But as recently as the 1970’s, Lawrence Simonds, who owned two restaurants in Norwich, would take food to Eliza George, the grandmother of Richard A. (Skip) Hayward, chairman of the Tribal Council, said Lawrence Simonds’s daughter Joan Simonds.

Eliza George, who died in 1973, was the sole resident of the reservation from the late 1960’s through the mid 70’s. For most of the 20th century, the Mashantucket Pequots had no cohesive tribal life, Joan Simonds said. Although the family would go to Narragansett and Mohegan powwows, there were no Mashantucket Pequot gatherings to go to, she said.

By 1974 the Simonds family started hearing about the tribal organization being formed by Mr. Hayward. In 1975 he was a young man who had moved back to the reservation and was forming a tribal government composed of members of his immediate family.

A year later, Mr. Hayward invited a group of his cousins to the tribal land and revealed his vision for rebuilding the tribe. The Simonds, who are not related to the Georges, were not invited.

“You better believe I’m angry,” Joan Simonds said. “It is the history of my people that is being exploited by the people who now call themselves Mashantucket Pequot. It is my heritage which is being exploited for greed.”

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, several Mashantucket Pequots — all George-family descendants — answered Mr. Hayward’s call to return to the reservation.

But it was not until the Foxwoods High Stakes Bingo and Casino opened in 1992 that the population exploded. In the last three years, the tribal roll has more than doubled, with about 370 people now considered official members.

In Norwich, Lawrence Simonds’s son Larry, a 44-year-old antiques dealer and real estate broker, watched in amazement as his once-dormant tribe grew bigger and richer than anyone could have ever imagined.

With part of its proceeds, the tribe commissioned and published a book documenting its history. In the book, “The Pequots in Southern New England: The Fall and Rise of an American Indian Nation,” Larry Simonds found a description of Immanuel Simons. He was called an important political leader in the 18th century who successfully helped fight attempts by the state and neighbors to encroach on reservation land.

Susan Simmons is described in the book as a leader of “one of the core families, who maintained an active role in the political and social life of the Mashantucket Pequot community” during the 19th century

Despite no written tradition among pre-Columbian Indians, and no fixed spelling of names during Colonial times, Larry Simonds had good documentation that these people were his ancestors, and family lore says the Simonds are descendants of Robin Cassacinamon, the Mashantucket Pequot’s first leader.

In May 1993, Larry Simonds submitted an application for tribal membership. Despite intervention from a tribal lawyer and a visit from a member of the Tribal Council last summer, he’s still waiting for a response. “Its real hard to believe that they don’t have the time or opportunity to look at our application,” he said.

During the groundbreaking and ground blessing ceremony the Mohegan Tribe held for their planned Mohegan Sun Casino, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe was represented by Kenneth M. Reels, vice chairman of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Council.

“The Simonds have Mashantucket Pequot ancestry,” Mr. Reels conceded when questioned by a video reporter during the ceremony.

However, Mr. Reels said the Simonds could not become members of the tribe until the tribe’s membership and tribal council decide to amend the tribal constitution’s membership laws.

But the tribe’s lawyer, Jackson T. King Jr., said in an official tribal statement last summer: “The Mashantucket Pequot Tribe has established criteria for membership through its constitution, which was accepted by the United States Government in its 1983 recognition of the tribe.”

“The Simonds family does not meet those criteria,” he said.

Because the membership criteria were set and accepted by the United States Government, the Simonds will bring their case to Federal court, Joan Simonds says. Membership laws that arise internally in a tribe cannot be challenged in Federal court even if they violate Federal civil rights. But because the Federal Government was a party to the formation of the tribe’s membership laws, and because the Simonds can argue that their Federal civil rights have been violated as a result of Federal action, the Simonds can go to Federal court, Ms. Simonds says.

“This isn’t just about money,” said Luther Simonds, a 58-year-old automobile sales manager from New London, who is first cousin to Larry Simonds and Joan Simonds. “Whatever the Mashantucket Pequot have, the contributions of the Simonds, the heritage of this family, my ancestors, played a big part of it.”

He is especially upset because 1858 Mashantucket census lists were part of the tribe’s application for Federal recognition, and records dating to 1855 were the basis for a Federal land claims settlement that in 1983 allowed Mr. Hayward and his relatives to take land that once was occupied by ancestors of the Simonds.

Simonds family members also are angry because the rules of membership have changed over the last 20 years.

In 1974 they would have qualified easily. The bylaws defined a lawful member as any person “who can prove through a birth certificate or other legal record that he or she is directly related to an Indian who is genealogically recorded as a Western Pequot Indian by the State of Connecticut.”

In 1977 the bylaws were changed to require members to prove that they were one-eighth Indian — any kind of Indian.

That requirement would have included the Simonds, because in addition to Mashantucket Pequot, the family also claims Narragansett, Wampanoag and Mohegan ancestry. It wasn’t until 1984 that the requirement that excludes the Simonds was adopted.

One of the family’s complaints is that in 1990, when a Mashantucket Pequot burial ground dating from 1666 to 1720 was disturbed during construction at a site off the reservation, the tribe reburied the bones without consulting the Simonds.

The Indian Repatriation and Reburial Act, a 1990 Federal law, required the George family to notify and consult with the Simonds family before reburying the remains, said Joan Simonds. This was not done, she said.

The family is trying to bring a lawsuit in the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Court claiming the remains are more likely to be from ancestors of the Simonds than they are to be the remains of ancestors of the George family.

The Simonds are prepared to submit United States Bureau of Indian Affair documents showing that ancestors of the Simonds family were listed as residents of the reservation in 1759 while definitive ancestors of the George family are not documented as residents of the reservation until 1900 and 1910.

On Nov. 3, a member of the Simonds family read an open letter about the reburial issue at the tribal burying ground. The letter was addressed to the George clan and it read: “We are bringing this case regarding the reburial of the remains to the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Court to demonstrate that there is no Mashantucket Pequot culture, there is no heritage, there is no Mashantucket Pequot tribe without the Simonds.”

The letter continued: “The leaders of the so-called Mashantucket Pequot tribe say their purpose is not greed but the preservation of the blood, the heritage, the land. But every day the Simonds are denied justice it clearly shows their purpose is only greed.”